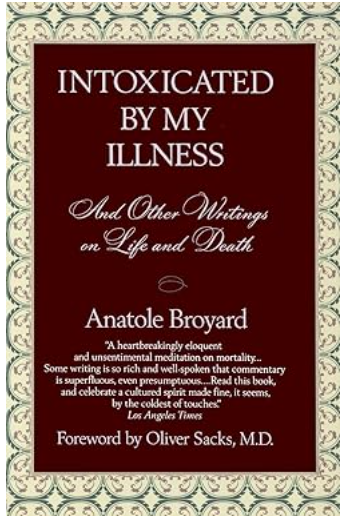

I first stumbled upon Intoxicated by My Illness by Anatole Broyard a few years ago while browsing through a bookstore. The title immediately caught my attention: Intoxicated by My Illness. I paused, intrigued. Being intoxicated by a great frozen margarita, sure—but by terminal illness? How could something that threatens to disrupt and erase parts of you be intoxicating? It felt both unsettling and deeply fascinating.

So, here’s the backstory. Anatole Broyard, who was a literary critic and editor for The New York Times Book Review, found out he had prostate cancer. Instead of simply enduring it, he decided to document his journey—reporting and analyzing his experience as both a patient in an often cold, impersonal medical system in the U.S. and as a person facing the reality of death.

And here’s where it gets interesting: Broyard claimed that this crisis, this confrontation with death, actually made him feel more alive. He described how his illness stripped away all the superficial worries and left him with what he called ‘raw ontological alertness.’ In other words, the illness sharpened his awareness of existence itself.

He didn’t shy away from describing the pain either. At one point, he said, “When the eight-inch needles thrust into my belly, I sensed them tickling my metaphysics.” It’s almost as if the suffering brought him closer to understanding some deeper truth about life.

This reminds me of what the German philosopher Martin Heidegger writes in Being and Time. Heidegger talks about how we usually get lost in the distractions of everyday life, as if we have all the time in the world. But it’s moments like Broyard’s, where you’re faced with something like a serious illness, that jolt you out of that illusion. You’re forced to see that time is limited, and you start to focus on what really matters.

Broyard offered a piece of advice to those facing terminal illness. He believed that in such situations, people need to develop a personal style—not just in living with their illness, but even in facing death. He wrote:

“… it seems to me that every seriously ill person needs to develop a style for his illness. I think that only by insisting on your style can you keep from falling out of love with yourself as the illness attempts to diminish or disfigure you. Sometimes your vanity is the only thing that’s keeping you alive, and your style is the instrument of your vanity. It may not be dying we fear so much, but the diminished self.”

In other words, Broyard saw style as a way to hold onto one’s identity and self-respect, even when the illness tries to take those things away. To him, having a sense of style is like holding onto a bit of pride—a way to stay connected to who you are, despite the physical changes and limitations that come with being seriously ill. It’s about finding a way to preserve your sense of self when everything else feels like it’s slipping away.

As a philosophical counselor, I often notice that people don’t realize how much their sense of self and personal meaning in life is built on the assumption that they’re healthy. Think about it—many of us love life because we have the capacity to pursue goals, work on projects, and imagine a future version of ourselves. Our relationships, too, are built on a certain balance of independence and interaction. But when a crisis hits, it can feel completely disorienting because it shatters those assumptions.

Suddenly, things we once did with ease are no longer possible. Projects we cared deeply about may no longer be viable. And even our relationships shift—we may find ourselves relying on others more than we ever thought we would, like needing help with something as simple as grocery shopping. These disruptions can leave us questioning not only what we’re capable of but also who we are without those capabilities.

Figuring out how to make sense of this, how to reorient your life and find meaning again, isn’t just a medical issue—it’s deeply philosophical. It’s about confronting those changes, accepting new limitations, and finding a way to live that still feels meaningful despite everything.

Philosopher Havi Carel describes illness as life’s forceful, even violent, invitation—pushing you into a situation you never asked for. Yet, within these constraints, a certain freedom still exists—the freedom to choose how you’ll respond, what attitude you’ll adopt, and whether to use this moment as an opportunity for reflection and growth. These choices, in turn, shape not only how we experience the situation but also how we move through it. Our responses can influence our journey, and in some cases, even affect the outcomes we face.

And this is where philosophy really steps in. Sometimes, when we’re going through something difficult—whether it’s illness or just a major life change—we need someone to help guide us through those deeper questions. That’s one of the reasons I offer email counseling. It’s a space where people can reflect on their lives, their challenges, and find clarity on their own terms.

If you’re interested in exploring these ideas more or would like to chat about your own experiences, I’ve left a link in the description below where you can learn more about the counseling services I provide.

The Patient Examines the Doctor

But Broyard’s reflections on illness don’t stop at his own experience—he goes further, exploring the critical relationship between patient and doctor, and how often, it falls short.

In Intoxicated by My Illness, Broyard includes an insightful essay called “The Patient Examines the Doctor,” where he reflects on the stark differences in how doctors and patients view illness. As someone battling a life-threatening condition, Broyard notices that his doctor seems completely out of sync with the gravity of the situation. The doctor, in Broyard’s eyes, is hearty, vague, and overly polite—completely missing the existential weight of what’s happening.

Broyard describes the disconnect: “There was no sign of a tragic sense of life in him that I could see, no furious desire to oppose himself to fate.”

He yearns for a doctor who understands the existential weight of his situation, someone who can see beyond the clinical facts and share in the profound emotional and philosophical struggle of facing mortality.

For the doctor, the crisis of Broyard’s life was just another routine incident during his rounds. But for Broyard, it is the ultimate emergency, a confrontation with the limits of his existence. “Ultimate” in every sense of the word—his health, his identity, his very life hang in the balance.

Broyard feels objectified under the “medical gaze.” He senses that he is reduced to nothing but his illness. Even his illness, he feels, no longer belongs to him but has become a subject of scientific inquiry. He notes that the doctor “was looking without looking.” The doctor sees him as a medical case, but not as a human being—one facing illness, potential death, and grappling with deep questions of fate, meaning, and identity.

This realization strikes Broyard deeply. He thinks, “I can’t die with this man.”

But Broyard doesn’t stop with criticism. He paints a picture of what he believes an ideal doctor should be—not just a skilled and potent professional, but someone who could see beyond his symptoms and body parts, who wouldn’t just treat his body, but also understand how illness transforms a person’s inner life, his sense of identity, and his struggle with meaning in the face of suffering.

He said, “I’d like my doctor to scan me, to grope for my spirit as well as my prostate,” “Inside every patient, there’s a poet trying to get out. … My ideal doctor would ‘read’ my poetry, my literature. He would see that my sickness has purified me, weakening my worst parts and strengthening the best.”

Broyard admits that he is asking for more than what most doctors are trained to offer. He understands that his expectations go beyond medical expertise. But he explains that “to be sick brings out all our prejudices and primitive feelings” and that “the craziness of the patient is part of his condition.” In other words, illness can push people into a state where they crave not just physical care but a deep, deeper, and deepest human connection. This is what human beings in these situations need—someone who can see the suffering behind the symptoms.

That’s why I recommend this book to anyone grappling with suffering in life-limiting conditions or reflecting on doctor-patient relationships in today’s hospitals. It offers a perspective that is both raw and insightful, shedding light on what it means to seek empathy and understanding when facing one’s own mortality.

As a philosophical counselor trained in the existentialist tradition, many of Broyard’s observations resonate with me.

Both doctors and philosophers aim to alleviate suffering, but they approach it in different ways. Doctors, by their training, focus on identifying the physical causes of pain. They diagnose, treat, and manage symptoms, with their primary duty being to understand the body’s condition and find ways to ease physical distress. Naturally, we hope doctors can also offer a more human connection, seeing patients as whole individuals rather than just cases. But expecting them to navigate each patient’s emotional, philosophical, and spiritual struggles might pull them away from their primary role—providing the best possible medical care without getting burned out themselves.

But suffering isn’t just physical. It’s something that has fascinated philosophers from East to West for centuries. It involves the meaning suffering holds for us, how it shapes our identity, and, at times, how to face a fate that cannot be changed. Philosophy helps us explore these deeper, existential aspects of our experiences and guides us toward a life that remains meaningful, even amidst pain.

For me, it seems like a balanced approach might be best—doctors to treat the physical, and philosophical counselors to address the existential, offering a holistic way to navigate both the body and the mind during times of crisis. What do you think about this combination of perspectives?

I’d love to hear your thoughts. Do you believe that developing a personal style in dealing with illness, as Anatole Broyard suggests, can help people facing difficult or life-threatening situations?

And what do you think—should doctors stick to their medical expertise, or should they also take on a more personal or even philosophical role, as Broyard envisions? What qualities do you think make an ideal doctor?

Let me know in the comments. Thank you for joining me today. If this resonated with you, please like, subscribe, and share. I’ll see you next time. Bye.

Related Readings:

- Anatole Broyard (1993). Intoxicated by My Illness: And Other Writings on Life and Death. Fawcett.

- Havi Carel (2016). Phenomenology of Illness. Oxford University Press.

- Martin Heidegger (1927). Being and Time. State University of New York Press

- Broyard’s Story

- An Article from Blackpast.org https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/people-african-american-history/broyard-anatole-paul-1920-1990/

- One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life–A Story of Race and Family Secrets by Bliss Broyard (his daughter)